When we say ‘this is a cat’, we mean that the idea of the cat is now instantiated, and that something we refer to as ‘this’ is identical to that idea insofar as it matches exactly the identifying characteristics that comprise the idea. ‘This’ may also match other ideas (for example: breed, name tag, microchip) which together differentiate ‘this’ cat from any other cat. If ‘this’ is not certain to be identical to the idea of the cat, we may say that it ‘looks like a cat’. If ‘this’ is certainly not identical to the idea of the cat, we can to some extent modify the idea of the cat to make the perceived characteristics identical with the modified idea. I argue that much confusion about the sense of identity (or what a thing ‘is’) arises from various interpretations of the possibilities of ‘this’. Some interpretations may be logically inconsistent, other can be consistently formalised but contingent, so when people argue about the identity of ‘this’ they may be talking past each another.

“If a and b are to count as the same, then a and b will have to agree in respect of all properties and relations, sortal properties themselves being among these properties.” (Wiggins, David. Sameness and Substance Renewed. Cambridge University Press, 2001, 56)

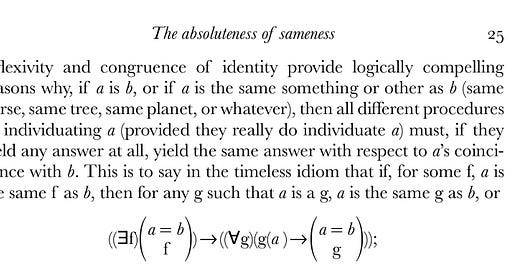

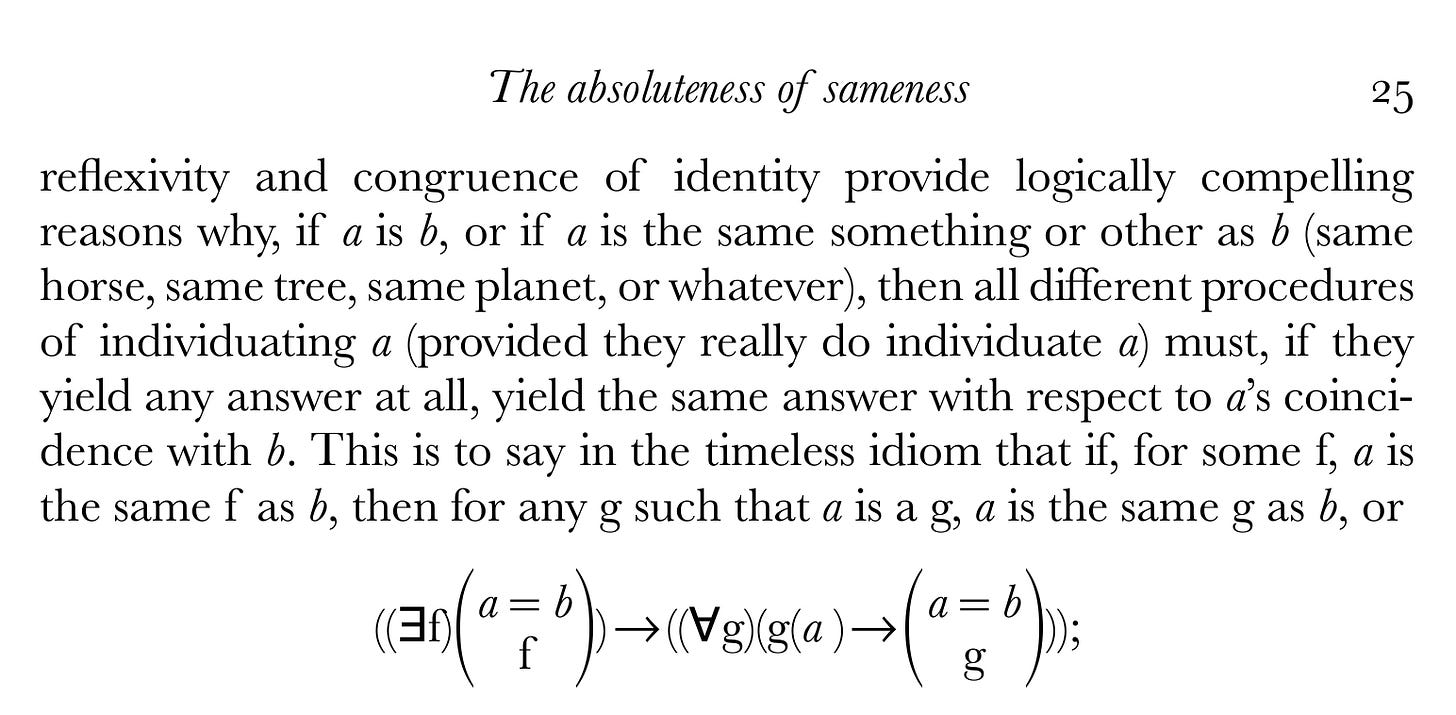

Peter Geach (Identity. The Review of Metaphysics, 1967) argued that x and y may be same f but a different g, or else the question of ‘what’ x or y ‘is’ would be unanswered and any statements of their identity rendered meaningless. David Wiggins argued that this cannot be, on the grounds of logical consistency (see the image above). I will consider the Ship of Theseus to contextualise these two views. Let x signify some ship at time t, and let y signify some ship at time t'. Both ships, or maybe the same ship, have the same crew who have not left their ship between t and t', but during that time they have replaced every piece of the structure of the ship with materials supplied by sea merchants. The crew believe that x and y are one and the same ship (because of the temporal continuity of their occupation and use: ‘the same f’). In contrast, the merchants who delivered the materials for rebuilding of the ship that existed at time t did not receive their payment and therefore insist that the ship at t' is their ship, entirely distinct from the ship at t. For the merchants, x and y are not the same ship (because they are made of different materials: ‘different g’). In other words, the sailors define the identity of x and y according to f, whereas the merchants do so according to g. We can thus interpret the argument of Geach as referring to different possibilities of conceptualising x and y, and the argument of Wiggins as referring to only one definition of x and y and insisting that any other definition constitutes a different thing (not x and y, since these names are already universally determined in their identity by Wiggins’ theory). The thesis in dispute is not consistently interpreted on the two sides of the argument: for Geach, the difference between f and g is precisely what makes x and y either the same or different (f and g are, in effect, sortal properties), which is sufficient to neutralise the proof produced by Wiggins (who assumes that x and y are already identified uniformly, in their purely symbolic, pre-sortal sense).

What advice could Geach and Wiggins give to the sailors and the merchants, according to their different theoretical positions? Geach's position can be interpreted as being above any social conflict about identity but engaging with the reality of the world that allows for contextualising multiple, conflicting interpretations. He could have said to the two groups: ‘Your dispute is arising from common experience, but you slice the same world in different ways and you will not come to agreement as long as you insist on your incompatible terms of discourse. You must first agree on what you are arguing about, what is the f and what is the g of your dispute.’ On the other side of the debate, Wiggins answers for himself (addressing a somewhat different, Hobbes' version of the story): “A simple conclusion suggests itself - that the best candidate theory, lacking obvious means to talk sensibly or intelligibly about plural candidates for identity, must cede place to a theory that identifies, for a given circumstance and a given question of identity, the best way to think of a thing and the best way to track the thing. Preferably this will be a theory that excludes, by its operation and application, the very possibility of distinct rivals for identity with Theseus' ship.” (Ibid. 99) In short, to interpret Wiggins’ account more specifically, ‘there is only one Ship of Theseus and the two groups are arguing about two different ships, hence there is no real problem of identity’. This does not seem very helpful, and since Wiggins excludes the possibility of mutually inconsistent accounts of identity pre-theoretically, his theory may be underpowered for this challenge. His analytical censure of Geach may have thrown the baby out with the bathwater, excluding the element that polarises the sense of common experience: our contingent conceptions of identity.

I will attempt to construct an account of identity that is compatible with the views of both Geach and Wiggins.

To say that A is a cat and B is also a cat, but B is not the same cat as A, implies that A and B are indiscernible according to the idea of ‘cat’ (what the term ‘cat’ means) but discernible according to some other idea (for example, ‘breed’). As such, to say ‘A is a cat’ we are not individuating A but individuating the sortal concept under which A can be individuated (which is the sense of ‘insofar’ at the beginning of this piece, be it f and g according to Geach, or a strict commitment to sortal identity according to Wiggins): there is a category for A that is identical to the idea of ‘cat’. More explicitly, ‘A is a cat’ is logically equivalent to ‘A belongs to a category, which is identical to the category Cat’. Similarly, ‘A and B are cats, but A is not the same breed of cat as B’ is logically equivalent to ‘A and B belong to the same category that is identical to Cat, but do not belong to the same category that is identical to Breed’.

Crucially, there can be no doubt about the sense of ‘is’ as that of logical identity/equivalence or formal equality (=), or else the sense of comparison, reference and attribution would be lost, therefore no sense whatsoever. Wiggins (Ibid. 99) explicitly acknowledges “the understanding of ‘=‘ that is implicit in everything we think and say about identity”, but this should go without saying unless explicitly denied. Rather, the only reasonable source of disagreements is the meaning of the terms that are equated by ‘is’ (as the same thing). In natural languages the relevant terms may only be implied, such as categories vs the contextually unique individuals that may belong to these categories. The category Cat is not identical to any individual cat, or else every different cat would be individually identical, the same cat, therefore contradiction; but any individual cat belongs to the category Cat, which is identical for every individual cat, and this is what we mean when we say ‘this is a cat’.

Moreover, individuation presupposes categorisation: categories are the meaning or substance of that which is individuated. Every individual thing can be conceived of only as a unique combination of kinds. Consider a visualisation of white noise. No object-boundaries exist in white noise, no-thing, but once we mentally freeze and isolate a portion of the noise, which is still just noise, we are able to compare it with other mentally frozen and isolated portions. Having isolated several portions in the same way, which are thus uniformly differentiated from unconstrained noise, we may commit this intentional difference to memory as a one kind of something, give it a name, which amounts to defining a kind. Thereafter, any newly isolated portion may be identified as a thing ‘of that kind’: the difference of the portion from everything else being identical to the difference that constitutes the kind.

The above does not yet adequately answer the question of ‘what is A?’. It was said that A is an identity of a kind, not yet the individual A, but the kind is also evidently constituted in terms of individual instances of that kind, possibly including A, which seems to imply constitutive interdependence of individual things and kinds, allowing both to change in time. This circularity need not be vicious or infinitely regressive, provided there is something essential that grounds the chain of reference. Referring to the example of white noise, it retroactively posits the idea of ‘white noise’ and of the original mental action of outlining a fragment from something unbounded. These ideas are abstracted from the categories that are already conceived of. Reflexive consciousness is the fundamental presupposition of all categorisation and their identification, but since consciousness presupposes itself it has the best claim to fundamentality, as the essential condition of everything else. We may nevertheless attempt to pursue the most fundamental category as that of Self and Other, since these are essential to reflexive consciousness. On a minimalist account, we have three essential elements: consciousness and, within it, the distinction between Self and Other. This implies that consciousness is (intrinsically) a mutually-contextualising multiplicity of the same kind, an original or fundamental kind, with no conceivable possibility of any deeper grounding. Consciousness, in its self-identity being mediated by other instances of the same kind, with no other means of differentiation or self-realisation, is the reference for everything, the ‘common’ property that locates us in the same world, even if we disagree on how to slice it into meaningful parts. The common experience of identifying and disagreeing about contingent identifications is itself a foundation of common identity.

Note:

A salient example that ostensibly fits the theory of identity proposed by Geach but not that of Wiggins is that of a naturalised migrant athlete (say, a Russian) who previously competed for his country of birth (Russia) and there became a national champion, may now be competing for their new country of citizenship (say, Australia) at the Olympics, and is promoted as an Australian champion, but at the same time is still identified just as a native Russian champion by his original (Russian) fans. Two different countries may claim someone as exclusively their own, one on the basis of the current citizenship, the other on the basis of ethnicity and the place of birth, and there is no way of logically invalidating one form of identity and preserving the other. On the other hand, if both identities are accepted as true in the same world, which, in the terminology of Geach, must be taken to have the function of a common language L of the theory T under which the identities are True, but are nevertheless mutually inconsistent, then both identity-claims are false. Another way, when identity-claims are mutually inconsistent, they are both invalidated, false, which in fact renders most of commonly made identity-claims false. Consequently I disagree with both Geach, who seems to maintain that all identity-claims can be true, and Wiggins, who claims that only one identity-claim can ever be true. My position is therefore that the only true identity is self-consciousness, and every other identity-claim does not have the sense of ’true’ identity but is only a subjective ascription to a contingent identity of some kind, which may be tentatively maintained, modified or rejected via intersubjective discourse/negotiations about common sense, which is a conscious process whereby ‘objective reality’ (the world ‘as we know it’) is generated, maintained, but is not constitutively definitive, complete or fixed. The process of world-creation is continuous.

Love the conclusion! I wonder what you would think about my series "Deus sive Qualia" as it also grapples with the fundamentality of consciousness.

Anyway great read!